Lacto-Fermented Vegetables

Get the ingredients right; Get the process right; Get the right result. Every time.

Background and History: What is Lacto-Fermentation?

Fermentation is defined as the chemical breakdown and transformation of organic matter by microorganisms and other microbiological factors such as yeast, bacteria and enzymes into acid, gas or alcohol. Lacto-fermentation, specifically, uses lactic-acid-producing bacteria (LAB), primarily from the lactobacillus genus, to break down the sugars in food to create lactic acid, carbon dioxide and sometimes alcohol. To put this simply, lacto-fermenting the juice of a gooseberry, for example, will remove any sweetness from the fruit and transform the juice into a silky, acidic and semi-dry component.

All you need is non-iodized salt, sugar (typically in the form of a vegetable or fruit), an anaerobic environment (i.e., a Mason jar or an airtight plastic bag), yeast (in this case, yeast from the skins of the food should suffice; so use organic), and a kitchen scale to weigh the ingredients. The salt keeps malevolent (i.e bad) bacteria from proliferating in the fermentation and ensures that the healthy LAB can do its job properly to create.

HISTORY

Lacto-fermentation, a timeless culinary technique, traces its origins across ancient civilizations. From Mesopotamia’s pickled vegetables to Asia’s kimchi and Europe’s sauerkraut, this practice of preserving food with beneficial bacteria has woven a flavorful tapestry through history.

Ancient Roots

As early as 6000 BCE, diverse cultures employed lacto-fermentation to preserve an array of vegetables. Cabbage, cucumbers, carrots, and even olives underwent this transformative process, not just for preservation but also for enhancing taste.

Global Traditions

Across continents, lacto-fermented delicacies became integral to regional cuisines. Mediterranean olives, Indian pickles, and Asian kimchi reflected the cultural diversity and ingenuity of fermenting a myriad of vegetables, infusing them with tangy, complex flavors.

Revival and Innovation

In recent years, a resurgence of interest in natural preservation methods and probiotic-rich foods has rekindled the fervor for lacto-fermentation. Modern kitchens explore inventive blends, from spicy pickled radishes to exotic fermented carrots, celebrating tradition with a contemporary twist.

Embracing Heritage, Shaping the Future

Today, as we revisit these age-old techniques, we honor their legacy by experimenting with diverse vegetables, spices, and creative combinations. The history of lacto-fermentation continues to inspire a flavorful journey that bridges ancient wisdom with modern culinary innovation.

Join the fermenting movement, savor the diverse flavors, and celebrate the heritage of lacto-fermentation!

Pickling Versus Fermenting: The Methods Compared

So, let’s take a good look at each method, starting with pickling:

Pickling is an ancient method of preserving vegetables by immersing them in a solution of boiling vinegar. The earliest record of pickling goes back to 4000 BCE in India. The hot liquid kills microorganisms on the food, including any probiotic “good guys.” The heat also destroys any enzymes in the vegetables. Acetic acid in the vinegar provides an environment that turns the vegetables sour. The acid environment also discourages spoilage organisms from growing back. Pickles will last for a few months at top quality flavor in the fridge. Before refrigeration, it was necessary to consume them within a few weeks for top quality.

Wild fermentation has been used for roughly 6000 years. The process hasn’t changed much in all that time. Fermented vegetables are chopped raw and placed in a vessel with a light, salty brine—usually about 2 or 3 percent salt. Filtered water is mixed with the vegetables’ natural juices to make enough liquid to keep the vegetables submerged. This has the immediate effect of keeping air away from the vegetables. Spoilage organisms like molds can grow on vegetables exposed to air, so submerging them is a crucial part of preventing spoilage. Initially, the brine solution is a mix of whatever microorganisms are on the vegetables or in the air when the fermentation vessel is filled. But within a few days, lactic acid bacteria turn sugars in the vegetables into lactic acid and a range of other delicious and nutritious compounds. The more lactic acid the bacteria produce, the more spoilage organisms are eliminated. Within a short time, the acid buildup cleanses the fermented mixture of all unhealthy organisms.

Those lactic acid bacteria also produce B vitamins as they metabolize the sugars. They create the spectrum of flavors that give fermented vegetables such palate appeal. In addition, they are the very probiotic organisms that colonize the gut and produce real health benefits. Among its other important functions, this gut microbiome enhances, strengthens, and even manages our immune system.

Pickling vs. fermenting? It’s the difference between a tasty sour treat of no great health benefit and a food that’s raw, rich in nutrition, alive with beneficial probiotics, and that beats pickles hands down for great flavor. In other words, no contest.

Recipe 1: Lacto-Fermented Carrots

Ingredients:

- 1 pound of fresh carrots, peeled and cut into sticks or rounds

- 2 cups non-chlorinated water

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

Process:

- Prepare Carrots: Clean and cut the carrots into desired shapes.

- Create Brine: Dissolve the salt in the non-chlorinated water to create a brine solution.

- Pack Into Jar: Place the carrot sticks or rounds into a clean glass jar, leaving some space at the top. Pour the brine over the carrots, ensuring they are fully submerged.

- Weight and Cover: Place a weight or a smaller jar on top to keep the carrots submerged. Cover the jar loosely to allow gases to escape.

- Fermentation: Store the jar in a cool, dark place for about 1-2 weeks, checking periodically. Taste to determine the level of fermentation you prefer.

- Refrigerate: Once fermented to your liking, move the jar to the refrigerator to slow down the fermentation process.

Reasoning:

Similar to sauerkraut, the salt brine creates an environment conducive to lactobacillus growth. The carrots, when submerged, ferment in the anaerobic conditions of the brine, resulting in tangy and probiotic-rich fermented carrots.

These basic lacto-fermentation recipes showcase the simplicity of creating flavorful and nutritious fermented foods using vegetables, salt, and water. The process harnesses the power of beneficial bacteria to transform ordinary ingredients into tangy, probiotic-rich delights.

Recipe 2: Lacto-Fermented Cabbage (Sauerkraut!)

Ingredients:

- 1 medium-sized cabbage (about 2-3 lbs)

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

Process:

- Prepare Ingredients: Remove the outer leaves of the cabbage. Core and finely shred the cabbage, placing it in a large mixing bowl.

- Add Salt: Sprinkle the salt evenly over the shredded cabbage.

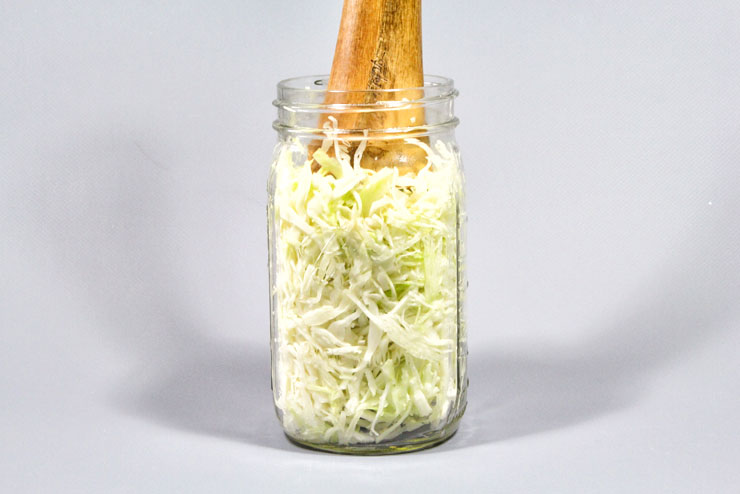

- Massage and Extract Juice: With clean hands, massage the salt into the cabbage for about 5-10 minutes. This process helps the salt draw out moisture from the cabbage, creating its own brine. The cabbage will begin to soften and release liquid.

- Pack Into Jar: Transfer the cabbage and any liquid into a clean glass jar, pressing it down firmly. Ensure the cabbage is submerged under its liquid.

- Weight and Cover: Place a weight or a smaller jar filled with water on top to keep the cabbage submerged. Cover loosely with a lid or a cloth to allow gases to escape.

- Fermentation: Store the jar in a cool, dark place for about 1-2 weeks, checking every few days. Taste occasionally until it reaches your desired level of tanginess.

- Refrigerate: Once fermented, store the sauerkraut in the refrigerator to slow down the fermentation process.

Reasoning:

The salt helps to draw out the moisture from the cabbage, creating an environment where beneficial lactobacillus bacteria can thrive and initiate fermentation. The absence of oxygen and the presence of a brine inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, allowing the lactobacillus to transform the cabbage into tangy sauerkraut.

FOR DETAIL: click on over to: The Sauerkraut-Specific Recipe

Recipe 3 - Zesty Fermented Bell Pepper Strips

Ingredients:

- 2-3 bell peppers (any color)

- 2 cups non-chlorinated water

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

- Optional: Sliced onion, garlic cloves, chili flakes, or herbs for added flavor

Process:

- Prepare Peppers: Wash the bell peppers, remove seeds, and cut them into strips or desired shapes.

- Create Brine: Dissolve the salt in non-chlorinated water to create a brine solution. Optionally, add flavorings like sliced onion, garlic, or herbs to the brine.

- Pack Into Jar: Place the pepper strips in a clean glass jar, layering them with any optional flavorings. Pour the brine over the peppers until they’re fully covered.

- Weight and Cover: Use a weight or a smaller jar to keep the peppers submerged in the brine. Loosely cover the jar to allow gases to escape.

- Fermentation: Store the jar in a cool, dark place for about 1-2 weeks, checking occasionally. Taste to determine the desired level of fermentation.

- Refrigerate: Once fermented to your liking, transfer the jar to the refrigerator to maintain the flavor and texture of the peppers.

Reasoning:

Similar to other lacto-fermentation recipes, the saltwater brine creates an environment for lactobacillus bacteria to thrive, transforming bell peppers into tangy and probiotic-rich delights. Optional spices and flavorings add depth to the final product.

Recipe 4 -- Sprouting / Lacto-Fermentation

This one’s experimental as shit. Make sure you sign the waiver, don’t feed it to your kids, etc etc

Details to follow

Troubleshooting

Fizz and Bubbles

Seeing bubbles in your jar? That’s the magic in action! It’s a sign that LAB are happily at work. Embrace the fizz, and don’t be afraid to taste as you go. If you’re doing anything where oxygen exposure is an issue, limit the tastings to a reasonable level.

White Film or Scum

A thin layer on top? No need to panic; it’s likely kahm yeast. Skim it off, and your ferment is likely just fine. Just ensure your veggies are below the brine to avoid any issues.

Color Changes

Colors might shift during fermentation – that’s normal. Enjoy the vibrant palette your veggies create as they transform.

Related Product Recommendations

Sources and other Neat Blogs

bango

bingo